We live in the age of the anniversary boom. We remember, commemorate or celebrate any and every newsworthy event from the past when it hits a significant milestone. Nothing epitomises that statement more than 2014. We’ve excelled ourselves this year in the attention we’ve given to the centenary of the First World War. The Great War book industry has never had it so good, with about 1,000 titles being published on the subject. The BBC commenced its mammoth plans to spend 2,500 broadcast hours covering the conflict until 2018. National institutions, such as the Imperial War Museum, have been transformed; whilst local projects have unfolded the length and breadth of the country.

But commemoration, just like our memories, is selective. We remember according to our needs and desires, not what actually happened in the First World War. And what has struck me, above all else, about this year, is that, for a society whose popular culture is so saturated in violence, we have been rather squeamish when it comes to remembering the bloody side of the Great War.

The activities, which have grabbed the most attention, have produced a remarkably sanitised version of events. The Christmas truce seems to know no bounds in terms of its popularity. Sainsburys gave it centre stage in its Christmas advert, leading to an outpouring of emotion and comment. The truce also inspired the ‘Football Remembers Week’, promoted by the Duke of Cambridge and featured in Ed Miliband’s Christmas message and the Queen’s Christmas speech.

There is no question that the downing of arms by two warring sides, on the most sacred day of the year, is an inspiring story. If the soldiers did play the beautiful game, then the game can never have been more charming. But the Christmas truce is wholly unrepresentative. On that day, as well as the other four years, three months and 14 days that made up the conflict, most soldiers followed their orders and fought, maimed and killed for their country. They were, after all, at war.

The way in which we commemorated the start and end of the war also effaced the horrors that lay between those two dates. ‘Lights out’, quite appropriately, plunged the UK into darkness at 10pm on 4th August, but the single light then left on seemed to almost romanticise the occasion.

The poppy installation in the Tower of London moat, which attracted an estimated five million visitors, was also, in itself, a beautiful sight. What it represented was not pleasant at all. Each poppy was a symbol for the 888,246 war dead. Yet, even our focus on the war dead, serves to sanitise the conflict. This may sound perverse but, by remembering the dead, we forget the dying. It becomes too easy to overlook the minutes, hours, days, weeks or years of writhing pain some, maybe many, of these men endured, before they became, in the Cenotaph’s words, ‘glorious’.

When I saw the Tower of London moat, I wondered about Lieutenant Francis Hopkinson. He was wounded in the Third Battle of Ypres on 12th August 1917. He had his left leg amputated three times and was hospitalised for shell-shock. He lived in severe pain, due to his agonisingly tender stump, until the age of 85. When I saw the stirring images of the poppy installation, I wanted a poppy for Hopkinson with the date of his death embossed on it: 17th December 1974. It would force onlookers to think of the tortuous decades thousands continued to endure.

I could suggest many reasons for our desire to sanitise the war. One might be because we are now so strongly connected to the conflict. We are linked to it in a cultural sense, whether through the poetry taught in schools, or best-selling novels, or much-loved television series, such as Blackadder Goes Forth. We are also connected to the war in a personal sense. Most of us have had grandparents and great-grandparents who fought in the war. As a result, we feel some proximity to it. But, since none of those people are still living, the First World War can now be our war. It belongs to each of us, as much as to anyone else. It is unsurprising that we prefer to associate ourselves with acts of humanity, rather than ones of aggression.

Our preference for remembering the dead, rather than the war wounded, may stem from the fact that the dead are not our responsibility. Men, such as Hopkinson, lived in our lifetimes. Remembering them entails our potential culpability, what more we could have done to alleviate their suffering.

Instead, our focus upon the dead of the First World War has become an end in itself in 2014. I’ve felt somewhat blasphemous asking what I think is a highly relevant question. What are we remembering them for?

This question is so important because how and why we remember has bearings on the choices we, and our government, make.

We are still going to war. We have a responsibility to stare squarely at all aspects of war, as we continue to choose to enter into more conflicts.

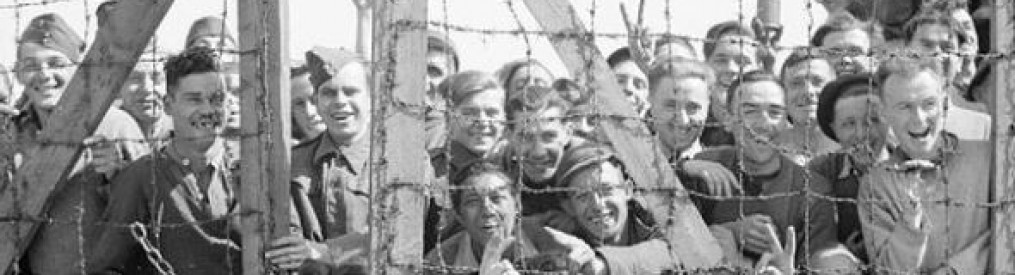

When we remember the First World War, we should remember everything. We should remember the dismemberment, disfigurement, the disembowelment that combatants went through, and not lose those graphic sights in symbolisation. We should remember the bloody acts of violence, revenge, even murder, as well as the inspiring gestures of humanity. We should remember not just the dead but those who bore war’s devastating physical and psychological scars, long after the conflict ended.

We should remember all of it and all of them. We owe it to them, and to us.